I have a wonderful friend Monica who is an artist and therapist. She helped me put together a program a few years back called “Creating Peace by Creating Space,” where we talked about the psychological implications of clutter and the importance of organizing for your mental health. Monica started the workshop with the following exercise which helps you understand how clutter affects you.

ASK YOURSELF…

1. Where do you feel peaceful?

What is it about that space that helps you feel that way?

What does it look like?

Where you are in the space?

What is the light like?

What are the textures of the space and the colors?

What are the things in that space, and how do you see them?

2. Where do you feel stressed?

What is it about that space the makes you feel that way?

What does it look like?

What is the lighting like?

How much room do you have to move?

Are you alone or with others?

What are the things in that space, and how do you see them?

3. How does your environment, the space you spend the most time, affect your well-being?

If you are like most people, the places where you feel stressed are cluttered. If your home is cluttered, it cannot be a peaceful retreat. That isn’t to say that your environment needs to be minimalist in order to be peaceful. The space, as well as the things in it, need to bring you peace.

During the pandemic lockdown, my organizing business (like many other businesses) disappeared because people couldn’t invite me into their home. Such irony, since there was suddenly plenty of time and opportunity for people to organize their home. Some people took the opportunity to declutter their closets and get rid of old clothes and toys on their own. Some cleaned up the backyard or attempted to tackle the dreaded garage. Being at home forced people to look at what was there. But for many, looking at what was there was depressing and it was easier physically and emotionally to just shut the door and watch Netflix. Sound familiar?

How Clutter Affects Us

During our workshop, Monica shared that not only is she affected by clutter, she is affected by anything being in the wrong place where it doesn’t belong. Her family does not experience the environment the same way. They are what she calls “collectors” and they leave “trails.” So, to escape the anxiety of clutter, she created her own “retreat” which started as a corner of the living room in which to have coffee in peace, and now has become a full-blown artist studio built in her backyard. What is it about clutter that gives us anxiety and makes us stressed?

Clutter makes us anxious because the piles seem never-ending. It’s more difficult to relax because it signals to our brains that our work is never done. I often feel guilty when I want to watch something or work on my hobbies because there is so much to do.

Clutter pulls focus and reduces productivity. It draws our attention away from what our focus should be because our brain needs to work overtime to respond to excessive unnecessary stimuli. Clutter invades the space we need to dream, create and problem-solve.

Clutter affects our relationships. It impedes our ability to find things quickly, so we arrive late, miss deadlines, and inconvenience people. We tend to apologize a lot. We feel ashamed because we think we should be more organized. We have this idea in our head that our self-worth is dependent on the tidiness of our home, and so we feel “less than.”

Clutter hurts our social life. Our home should be a place to feel pride. Instead, we are reluctant to invite people over because we don’t want people to judge us by our clutter, and we are embarrassed when people drop by.

Clutter leads to unhealthy eating. Research at Cornell University showed that people will actually eat more cookies and snacks if the environment in which they’re offered a choice of foods is chaotic, and they’re led to feel stressed. When the experimental kitchen in which participants were tested was disorganized and messy, and they were put in a low self-control mindset, students in the lab ate twice as many cookies as those in a standard, non-chaotic kitchen. In other words, you’ll reach more for the sweets in a cluttered setting when you’re feeling out of control.1

Clutter makes it harder to read people’s feelings. In an examination of the impact of clutter on perceptions of scenes in movies, researchers in a 2016 study at Cornell University found that when the background of a scene is highly cluttered, viewers find it more difficult to interpret the emotional expressions on the faces of the characters. Applied to daily life, this means that you’ll be less accurate in figuring out how other people are really feeling when you’re seeing them amidst a clutter-filled room.2

Clutter contributes to memory problems. I’m not just talking about losing your keys because they’re hidden under a pile of papers. University of Toronto's Lynn Hasher research suggests that mental clutter is a leading cause of age-related memory losses. The visual distraction of clutter increases cognitive overload and can reduce working memory. If material is clogging your neural networks, you’ll be slower and less efficient in processing information. Then when you have to come up with information you should know, like names and nouns, you may no longer find this information or access it quickly.3

I used to be a computer teacher so think of it this way: Your brain is like a computer. If there are too many tabs open at one time (visual clutter), your processor will run slower. Plus, all those extraneous tabs take up storage space so there is less space to move around and access the important files you have stored.

Your Brain on Clutter

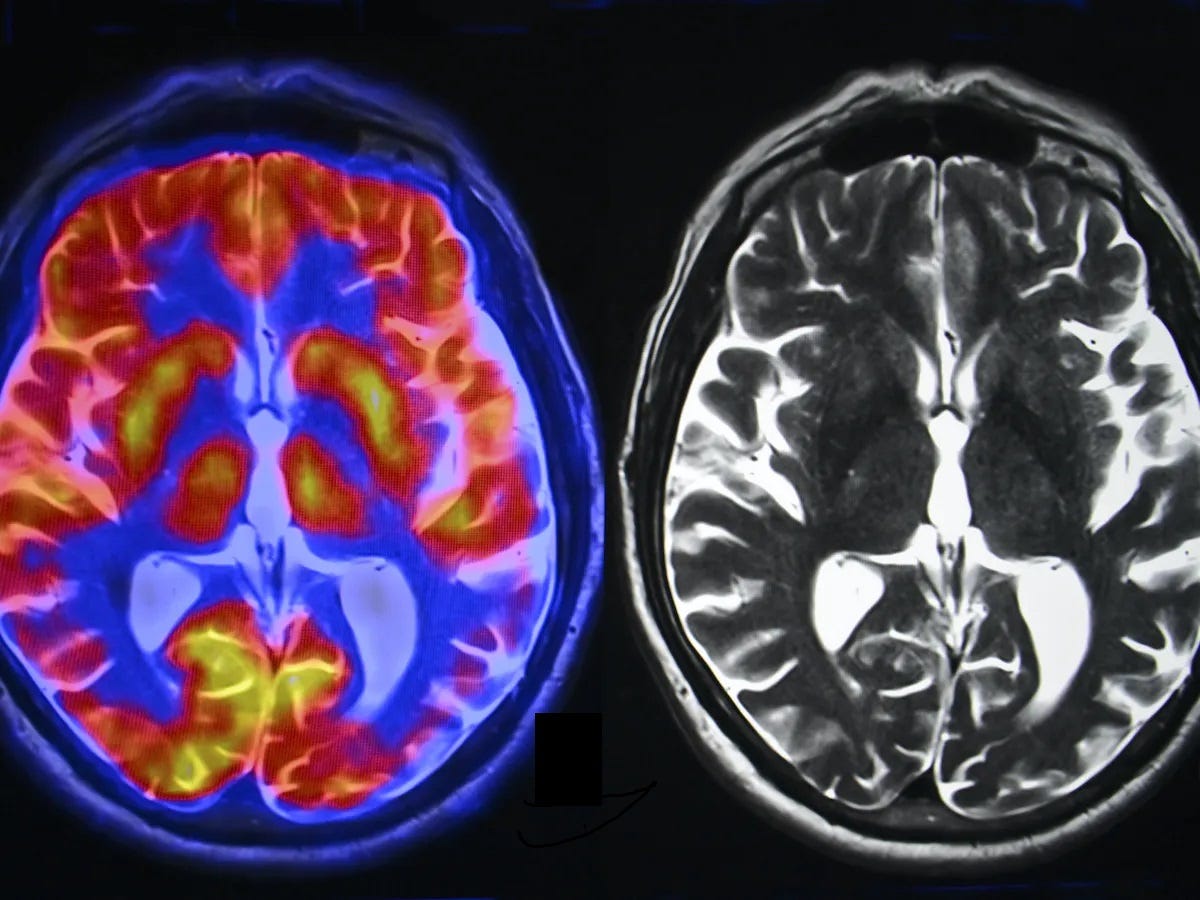

Remember the commercial about your brain on drugs? This is your brain on clutter.

You are home, and instead of feeling safe and peaceful, your senses are working overtime, taking in the mess. The amygdala (the part of your brain that processes emotion) perceives a stressor (clutter) and signals the hypothalamus to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, which prepares the body to respond to the threat. The adrenal glands release stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol into the bloodstream, forcing you to stay tense and alert and causing the reaction to Fight, Flight or Freeze.

Fight - you “tackle” the clutter, or you get angry and argue with the people making the mess

Flight - you shut the door, avoid the job and distract yourself with something else

Freeze - you are paralyzed and overwhelmed - you don’t know how to start so you take a nap and nothing gets done.

Stress Changes Your Brain

Now imagine if you are in a chronically cluttered environment and constantly in that state of tense, high alert. There has been a lot of research into the harmful effects of stress on your brain. As if you weren’t stressed enough before, check this out.

Stress Changes Brain Structure. It upsets the balance between gray and white matter which can result in long-term changes to brain structures and function.

Stress Kills Brain Cells. It produces high levels of

tisol which kills new neurons in the hippocampus – an area of the brain associated with learning, memory, emotion and where new brain cells are formed.4

Stress Shrinks the Brain. It reduces grey matter in the prefrontal cortex - the area associated with memory and emotional regulation.5

Increases the Risk of Mental Illness: People who undergo prolonged periods of stress are more prone to suffer from mood and anxiety disorders later in life because of long-term changes to the brain.

So here’s the main takeaway:

Mess causes stress. Stress adversely affects your brain, memory and mental health. Your mental health affects your physical health. Therefore, an ongoing practice of organizing is just as important as meditation, exercise and diet for your overall well-being, and the well-being of the people you live with.

Vartanian, L. R., Kernan, K. M., & Wansink, B. (2017). Clutter, chaos, and overconsumption: The role of mind-set in stressful and chaotic food environments. Environment and Behavior, 49(2), 215-223. doi:10.1177/0013916516628178

Cutting, J. E., & Armstrong, K. L. (2016). Facial expression, size, and clutter: Inferences from movie structure to emotion judgments and back. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78(3), 891-901. doi:10.3758/s13414-015-1003-5

Amer, T., Campbell, K. L., & Hasher, L. (2016). Cognitive control as a double-edged sword. Trends In Cognitive Sciences, 20(12), 905-915. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.002

Lucassen PJ, Pruessner J, Sousa N, Almeida OF, Van Dam AM, Rajkowska G, Swaab DF, Czéh B. Neuropathology of stress. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 Jan;127(1):109-35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1223-5. Epub 2013 Dec 8. PMID: 24318124; PMCID: PMC3889685.

Justin B. Echouffo-Tcheugui, Sarah C. Conner, Jayandra J. Himali, Pauline Maillard, Charles S. DeCarli, Alexa S. Beiser, Ramachandran S. Vasan, Sudha Seshadri. Circulating cortisol and cognitive and structural brain measures. Neurology Nov 2018, 91 (21) e1961-e1970; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006549